Documentation guidelines¶

how to help the user understand your work

Documentation is one of the big points on which you need to focus to allow your work to be usable by others.

In the course we mostly focused on the quality of the code:

- writing good quality code

- testing it to make sure it works properly

- create a good quality API

None of these actually allow the user to use your code: you need to explain them how!

Documentation is often a forgotten topic because it feels like a "chore": you already wrote the program, it works, your job is done!

Nothing further from the truth!

In a similar way to the tests, documentation should be part of the fundations of what you perceive your work to be when programming, and done alongside the code in the same way as the tests.

Target users¶

there are three different kind of user for which to write documentation:

- users of the program/library

- developers/contributors

- reviewers

they have very different needs, and you should have clear which one is your target when you are writing a piece of documentation

The first rule for documentation is that it should be usable and available

Usability¶

The user should be able to understand it and explore it.

- no abstruse sentence

- properly written

- available in commonly spoken languages

- in a data format that can easly be accessed

About the data format, I strongly suggest to have all the following:

- inside the program itself (help menu)

- as structured text (Markdown or RestructuredText)

- html pages

given that it is easy to generate HTML from structured text, I would reccomend to get comfortable using them.

For GitHub the default is MarkDown, while for python documentation is usually RestructuredText.

I personally prefer RestructuredText as a language, but Markdown is simpler and more commonly used, so it is a better starting point. (https://github.com/adam-p/markdown-here/wiki/Markdown-Cheatsheet)

Availability¶

Available means that the user should be able to find it.

inside the program¶

inside the program means that it is always available

Particular value is the contextual help if the user is having trouble figuring out the procedures

it should also link to the online material for more extensive documentation!

it might not be available, as one might not be able to run the program!

online documentation¶

should be comprehensive of everything!

from every page there should be a way of navigating links to reach any other

Give multiple path to reach the information!

Documentations types¶

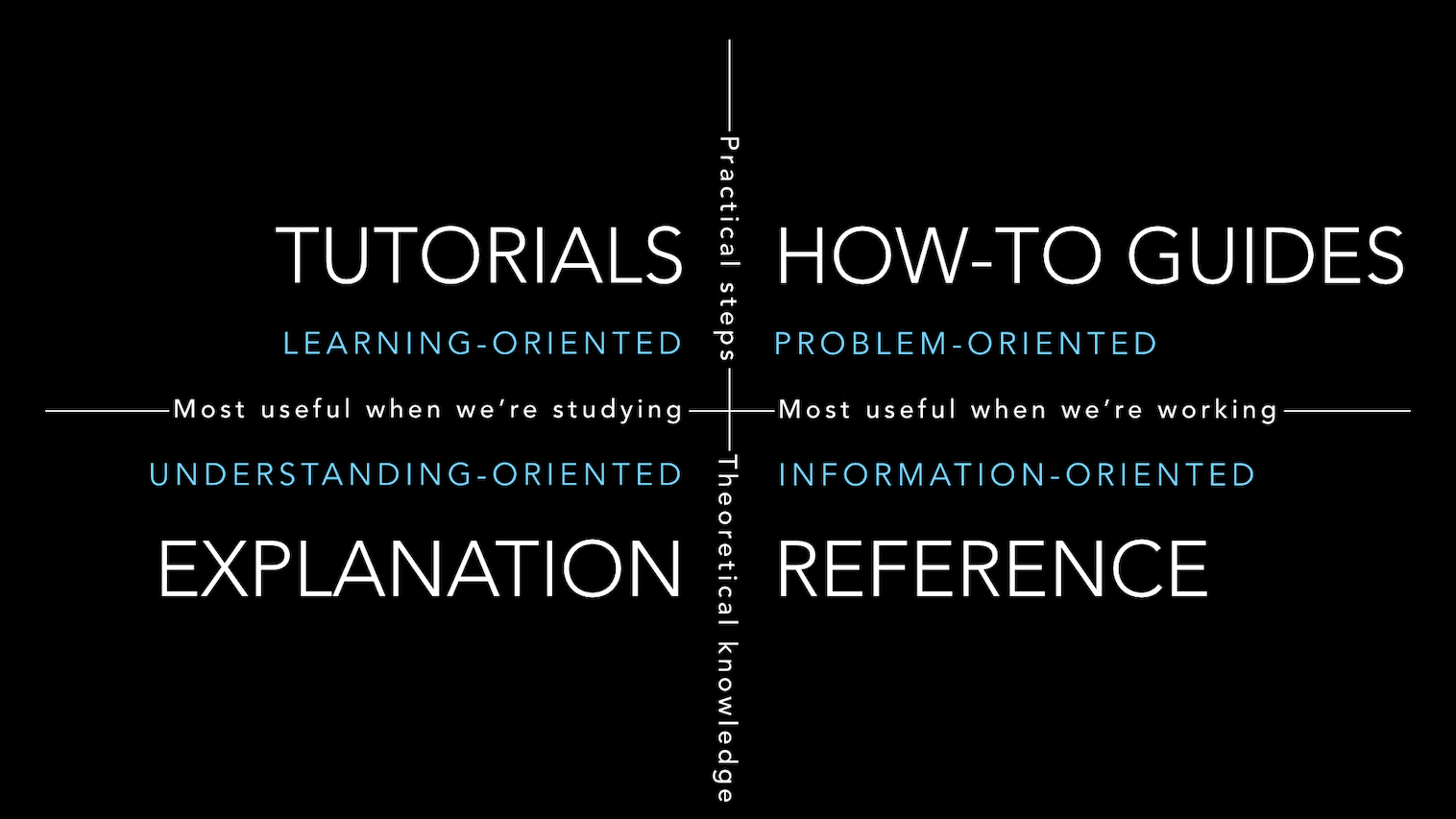

Theory of documentation for users brought forward by Daniele Procida (https://www.divio.com/blog/documentation/)

it divides the documentation in 4 distinct kind of documents, each one with its own goal:

- tutorials: guided learning of the basics

- how-to guides: assume complete knowledge, show how to best solve a problem

- reference: details about the API, functions names, parameters, etc...

- explanation: the theoretical background and design decisions

Each of the quadrants is similar to its two neighbours:

- tutorials and how-to guides are both concerned with describing practical steps

- how-to guides and technical reference are both what we need when we are at work, coding

- reference guides and explanation are both concerned with theoretical knowledge

- tutorials and explanation are both most useful when we are studying, rather than actually working

Jupyter notebooks¶

Jupyter notebooks are great tools for writing documentations, in particular tutorials (such as the slides of this course), as they allow to intermix code and markdown-formatted text.

Personally I don't like as development tool, but I find them amazing as a teaching tool (for your users).

It is easy to generate html or markdown files for your documentation from the notebooks, and I suggest you consider doing it!

jupyter nbconvert --to html MyCoolNotebook.ipynb

jupyter nbconvert --to markdown MyCoolNotebook.ipynb

jupyter nbconvert --to slides MyCoolNotebook.ipynb

Pandoc¶

pandoc is a program that can be installed using pip and that allow to easily convert between different file types, such as markdown and docx, or latex and pdf.

pandoc --from=markdown --to=docx --output=test.docx .\Lesson_AF_08_Documentation_and_API.md

Documenting Code¶

this kind of documentation is necessary for anybody that have to understand and take care of the code in the future.

might be other researcher, random people on the internet, or yourself few months from now!

for python, the most important ones are:

- docstrings

- typing

- comments

- the code itself

docstrings¶

IDE like spyder already can create a suggestion of the simplest informations that one needs to put

need to have:

- short one sentence description of the function

- long function explaination

- input and output, expected types and meaning

- potential exception raised in the code

good to have:

- example of usage of the function

- relationships with other functions

- explaination of the theory

- references for the theory

One should provide docstrings for:

- each module

- each function in the module

- each class in the module

- each method of each class

- each test in the test suite (but use the BDD description style instead)

numpy docstring standard:¶

https://numpydoc.readthedocs.io/en/latest/format.html#docstring-standard

typing¶

now that python include a semi-decent typing system, leverage it!

just remember to keep types as general as possible:

- sequences instead of list, unless you use a list specific function

- mapping instead of dictionaries

- numbers instead of ints and floats

describe types of input and output, it allows you to:

- inform the user of what you can take, removing the need for explicit checks (and the associated unit tests)

- allow to use automatic code checking tools

- keep track during development of what every object should be

- modern IDE can do type inference and provide autocomplete and suggestions

Python is a dynamic language, but is still strongly typed. One just don't have to declare the typed beforehand.

What they introduced is the possibility to annotate the code to express expectations over the type of variables, arguments and functions.

This does not have any effect on running the code, but allow type checkers (the most famous one is mypy) to assess if the code is correct

to test your typing you can use the mypy application:

mypy my_file.py

for example, the following code have a lot of issues, but they migh not be immediately apparent just looking at it.

If we don't put any typing information, mypy doesn't complain and doesn't do anything

%%file test.py

def eleva(n):

return n.upper()

dati = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for dato in dati:

print(1+eleva(dati[dato]))

Overwriting test.py

!mypy test.py

Success: no issues found in 1 source file

I can start introducing types informations and will find progressively more possible mistakes.

types are specified with a colon (:) after the argument or variable, followed by the type object that it should have.

for the return type, one can use an arrow ->

%%file test.py

def eleva(n: str) -> str:

return n.upper()

dati = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for dato in dati:

print(1+eleva(dati[dato]))

Overwriting test.py

!mypy test.py

test.py:8: error: Unsupported operand types for + ("int" and "str") test.py:8: error: Argument 1 to "eleva" has incompatible type "int"; expected "str" Found 2 errors in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

%%file test.py

from typing import List

def eleva(n: str):

return n.upper()

dati: List[str] = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for dato in dati:

print(eleva(dati[dato]))

Overwriting test.py

!mypy test.py

test.py:7: error: List item 0 has incompatible type "int"; expected "str" test.py:7: error: List item 1 has incompatible type "int"; expected "str" test.py:7: error: List item 2 has incompatible type "int"; expected "str" test.py:7: error: List item 3 has incompatible type "int"; expected "str" test.py:10: error: No overload variant of "__getitem__" of "list" matches argument type "str" test.py:10: note: Possible overload variants: test.py:10: note: def __getitem__(self, SupportsIndex) -> str test.py:10: note: def __getitem__(self, slice) -> List[str] Found 5 errors in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

this allows me to annotate only the code I care about without having to deal with typing everywhere

I can specify more complex types using the library typing, that allows to specify very complex structures

I would suggest also to leverage the user-defined types to future proof your code, and make it more explicit in its intentions

from typing import NewType

UserId = NewType('UserId', int) # declare a variant of ints used to user IDs

some_id = UserId(524313) # it is still an int!

leverage generics to express general relationships when working with containers. Also, when possible always specify the type contained inside the containers!

from typing import Sequence, TypeVar

T = TypeVar('T') # Declare generic type variable

def first(l: Sequence[T]) -> T: # Generic function

return l[0]

if you find that writing the type declaration of a function is too complicated, probably you should break the function into smaller chunks!

a note on typing readability¶

Having a lot of typing in you functions and methods could quickly lead to a perception of low readability, due to the "noise" that the type declaration adds.

there are two solutions for that:

- following an appropriate coding style

- giving types a descriptive names

descriptive names¶

as discussed earlier, nothing stops us to assign a name to a type and use that in our code

%%file test.py

from typing import Iterable

data_list = Iterable[int]

def eleva(n: str):

return n.upper()

dati: data_list = [1, 2, 3, 4]

for dato in dati:

print(eleva(dato))

Overwriting test.py

!mypy test.py

test.py:12: error: Argument 1 to "eleva" has incompatible type "int"; expected "str" Found 1 error in 1 file (checked 1 source file)

coding style¶

a commonly recommended coding style (such as the one enforced by black) suggests to put all arguments of a function in a new line, with one level of indentation, and a new line with the closing parenthesis.

This gives plenty of space for typing informations and ad-hoc comments

following these kind of guideline, a function written as:

def my_function(arg_1, arg_2, arg_3, arg_4, args_5):

"""docstring"""

function body

would be rewritten as:

def my_function(

arg_1: type_1, # some comment

arg_2: type_2, # more comment

arg_3: type_3, # let's discuss this

arg_4: type_4, # I used this name because ...

args_5: type_5, # etc...

) -> return_type:

"""docstring"""

function body

This approach is also way more friendly for version control, as it allows to recognize modifications to single arguments in the diffs.

IMPORTANT: there are variations and preferences in this, do not feel restrained!

you can read a more detailed argument here, from the writer of black:

comments¶

comments can be seens as a form of documentations as any other, but with the developer in mind instead of the user.

the following is my personal opinion:

- try to be conservative with the number of comments you write

- focus on "why" and not on what

- use them to fill the "negative space"

focus on "why" and not "what"¶

if the code is written with good style, and read by someone half competent, describing the line of code in a comment is redundant at best

# increase the width by 1

width += 1

explaining why a piece of code exists, is way more important

# need to increase the width of the window to compensate a off-by-one

# error due to the window management system (see bug#12345)

width += 1

code negative space¶

related to the idea of self-documenting code.

even the most readable code can't explain why some code IS NOT THERE.

one needs comments to explain:

- why certain "expected" procedures have been removed by a piece of code

- what approaches has been tested but failed, and why

comments with markup¶

most IDE recognize comments that contains specific markups, and they are very useful to keep track of the state of code.

some commonly recognized ones are:

- TODO - there is some code that should be put here

- FIXME - there is a known error case, but not implemented yet

- HACK - solve an issue, but is a sloppy way, improve if possible

- BUG - there is a problem in this point in the code, but the solution is not clear

- NOTE - some information about the following code

for example a reference can be found in the (rejected) PEP 350:

many systems are able to render also the markdown in these comments, so feel free to leverage them!

- [x] SLA

- [ ] Contact Info

- SLA

- Contact Info

self documenting code¶

This is the hardest level to reach, but also one you shold strive for:

writing code with clear name and relationships, that allow to understand what is happening by just reading it

- Everybody wants to do it (because it sounds less effort than writing documentation... Oh, my sweet summer child!)

- most think they manage to

- almost everybody fails (and I'm being generous by using almost).

One should still aim to reach this state, and it is always good to refactor to get closer to this state

Documenting Changes¶

This is for developers and users alike: if you change your library/program, explain what has been changed.

your goal is to improve your code over time, but also to allow your users to keep using it proficently

- semantic versioning

- changelogs

semantic versioning (https://semver.org/)¶

The program version is a number or a string that is used to indicate the successive releases of the software.

I will explain here the so-called semantic vesioning, a widely used standard to convey informations about the compatibility of software over time.

It is not the only approach:

- many prefers to use the date of release

- there are many (valid) criticisms of a "pure" semver approach

basic structure¶

major.minor.patch

patch are simple changes that correct bugs in the code and don't change the API

minors are changes that are backward compatible (at least with the previous minor), don't change the general structure of the code, usually add features and expand the API

majors are changes that definitely breaks backward compatibility and possibily the structure and logic of the API

changelog¶

changelogs are documents describing the changes between versions.

Usually it's a document that is constantly updated, with the last realeases on the top of the page.

It's better to keep it updated while you write code, otherwise they will be overwhelming to write.

as a good practice, it is often a good idea to update the changelog with what you're planning to do before even doing, to help yourself to not stray off path and getting distracted

Usually they contains the following informations:

- bug corrected (possibly with reference to the the issue of the bug on the ticket management system, such as the github one)

- code improvement (performances)

- new functionalities

- extension of old API

- future deprecations

- deprecations

for the features that break old code, show example on how to convert it to the new version!

api evolution notes¶

- if you want to deprecate a features, always put a warning for at least one minor version to give time to your users

- small functions with small signatures are easier to evolve over time

suggested reading:

Documentation generation using Sphinx e readthedocs¶

- www.sphinx-doc.org

- www.readthedocs.io

Sphinx is a program that allows you to semi-automatically generate web-pages containing documentation for your code.

Readthedocs is a free hosting platform connected with github that provides a platform for the documentation of Open Source Software.

You will still have to write the documentation, they will not do magic for you!

!mkdir -p ./myapp/docs

Sphinx provides a quickstart program to setup your documentation is a simple-to compile way using a makefile.

%% bash

cd docs

sphinx-quickstart

once one accept the default and provides some basic info (such as the project name) sphinx will create the whole backbone of the documentation project

!ls ./myapp/docs/

_build conf.py index.rst make.bat Makefile _static _templates

the main two files are the conf.py and the index.rst.

index.rst is the actual home page, while conf.py tells sphinx how to compile it

!cat ./myapp/docs/index.rst

.. myapp documentation master file, created by sphinx-quickstart on Mon May 3 11:40:01 2021. You can adapt this file completely to your liking, but it should at least contain the root `toctree` directive. Welcome to myapp's documentation! ================================= .. toctree:: :maxdepth: 2 :caption: Contents: Indices and tables ================== * :ref:`genindex` * :ref:`modindex` * :ref:`search`

to create the actual web site, one just need to call make html from the docs folder

HTML("./myapp/docs/_build/html/index.html")

automatic docstring inclusion¶

sphinx can automatically load and parse the docstring (in rst format) that have been written

one needs to include in the conf.py the autodoc module:

extensions = ['sphinx.ext.autodoc']

and to document a module/function use anywhere in the rst files:

.. autofunction:: io.open

the module needs to be importable for sphinx to be able to parse it!

for example, once we install our module with pip --editable we could import on of the main functions as:

from myapp.__main__ import main_square

so to document this function we would put:

.. autofunction:: myapp.__main__.main_square

Once the documentation is ready, one can include it in the repository on github.

The next step is to make an account of readthedocs, from which one can import the documentation from the repository in a more or less automated way, and have it online and aligned with the latest version of the repository.

suggested read:

An introduction to Sphinx and Read the Docs for Technical Writers: